Too Long to Read

by Egatz

When did a comprehensive piece of quality writing become referred to as “a wall of text?” The United States has now developed into a culture feeling the need to apologize in advance for a longer article or story even before it’s read. Online forums and blog posts are often begun with, “Sorry for the wall of text, but….” When it comes to the written word, the American message is clear: Faster, less detail, and no analysis or historical context. These are the hallmarks our society values in the written word today.

When did a comprehensive piece of quality writing become referred to as “a wall of text?” The United States has now developed into a culture feeling the need to apologize in advance for a longer article or story even before it’s read. Online forums and blog posts are often begun with, “Sorry for the wall of text, but….” When it comes to the written word, the American message is clear: Faster, less detail, and no analysis or historical context. These are the hallmarks our society values in the written word today.

Casual readers are not alone in this continued search for brevity. People who edit for a living now send writers this message regularly. When did professional magazine editors begin returning stories to their writers, as happened to my friend David Biedny, with “TLTR,” shorthand for “Too Long To Read,” written in the margin? To paraphrase Frank Zappa, we’re dumb all over, and this isn’t good for our future.

The start date of the progressive dumbing-down of America is debatable, but there are culprits, and those culprits were largely enabled by electricity. Technologists can point to 1860, with the invention of the first mechanical analog audio format, the phonautogram. 1877 saw the more popular phonograph cylinder introduced. Thomas Edison offered the Ediphone in 1878, but recorded music took off with the music roll in 1883, causing chaos for the sheet music industry. These devices were bleeding-edge technology, and expensive, and by the release of the gramophone in 1895, music became the message they primarily delivered, not spoken text, speeches, lectures, or news broadcasts.

One can argue short attention spans really began when the first spoken threat to reading was born, in 1920, when Enrique Telémaco Susini began regular wireless entertainment broadcasts via radio waves in Argentina. In August of that year, Americans got their reading time diverted when E.W. Scripps was awarded a commercial broadcasting license in Detroit for WWJ, and used the airwaves to sell radios, much like HBO and Netflix creating their own programming to sell their service to subscribers. It was then the century-long death march of American publishing began in earnest. Suddenly, you didn’t have to work by reading to get your entertainment in the privacy of your own home. It was as good as having your terrified child humiliated as she tried to play the piano for your guests, only better, because you could now have professionals creating music, drama, and reading the news for you. By the way, those professionals got paid. More on this phenomena later.

After the talkies appeared in cinemas around the country, and later, when television invaded homes shortly after World War Two to become the cheapest daycare imaginable for the Baby Boomers, the micro attention span of Americans exploded into fashion with the advent of MTV in the early 1980s. A generation of teenagers became bored by anything longer than a five-second video edit. As if to make up for the lack of exceptional new music being created, music video directors—empowered by the speed and economy of editing on video decks, rather than having to splice film—decided to speed up the visuals to compensate for what many new recordings were lacking. If it didn’t flash and move fast, surely it must be old, boring, and, by association, not good.

By the late 1980s, the rest of the United States became addicted to the bombardment of 60-second segments on the 24-hour cycle of cable corporate news networks thanks to CNN, the first of its kind. Throw into this media-conditioning of the culture runaway diagnoses of attention-deficit disorders and the resulting push for prescriptions for children and adults of all ages, a proliferation of cable television channels, the liberation from broadcast television monopoly by the advent of VHS technology, the exploding video game industry, and an overworked middle class, and who the hell has time to read the written word, let alone a lot of written words?

It seems there’s just a handful of magazines capable of in-depth profiles and investigative pieces of real journalism. That may be an exaggeration, but it certainly feels that way. The lifespan of those publications is limited, of course, because most younger American readers can’t read anything longer than a menu, and older readers who expect well-written, detailed articles of substance are dying off. With diminished readership numbers come diminished advertising dollars. With diminished advertising dollars come diminished salaries and freelance rates. With diminished salaries and freelance rates come less writers willing to work for peanuts, as our grandparents used to say, or nothing at all.

I’ve lost track of the number of times weekly alternative newspapers, magazines, newspapers, and sites have asked me to write for nothing in the last 25 years. With my poems, I get it. In a country where a new volume of poetry selling 3000 copies is considered a bestseller, poets are expected to be given nothing and be thankful for it. As an editorial writer or journalist, it’s a different matter. No thanks, Ms. Editor. I’ve got some awards and plenty of publications under my belt. I don’t need “the honor” of my work appearing on your site (hello Huffington Post!) without renumeration. The co-op where I live—a collective of artists—doesn’t accept that “honor” in lieu of my monthly maintenance fee. As Mike Monteiro quoted the film Goodfellas, “Fuck you. Pay me.” More accurately, American writers who are often both crazy and passionate enough to write articles before they’re sold should be saying, “Fuck you. I did the work which will generate readers and advertising dollars. Pay me.”

For the last 100 years, each generation of Americans seem less capable of or interested in reading anything of length. I despair for those of you who’ve chosen to have children. Our education system has failed our nation from pre-school to college. I say that as a former undergraduate-level professor and the son of two teachers who retired as educational administrators (public school principal and college president). I taught college freshmen who couldn’t write two cohesive sentences in a row, and several who couldn’t read a passage aloud in my classes. Our local governments and the national government have failed our nation with biased, failed educational goals for decades. With an educational system that doesn’t teach high school graduates how to balance a checkbook or apply for a loan, not to mention think critically, how can we expect a new generation of readers to get excited over a New Yorker-length profile?

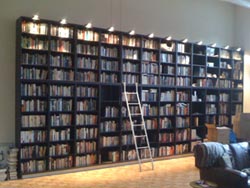

Of course, it starts before then. As each generation is awash in more electronic media, the importance of reading books—still the best long format delivery system—recedes further and further into the past. I was fortunate, with my parents somehow instilling a love of books and reading in me at an early age. Perhaps it was a good way to keep me occupied. Perhaps it was because I’m an only child: no siblings to fight or play with. Either way, I knew the written world was a magical escape hatch, but also quickly discovered it was an autodidact tool to teach me all the cool things never touched upon in public school. It became my oxygen supply, and by junior high school, I rarely watched television by choice.

With the Internet literally and figuratively in the pockets of most children, research doesn’t require reading books for the information a school report requires. Search engines help us zero-in on data to support points, which speed-up research infinitely, but something is lost when attention spans are conditioned to become shorter and shorter by not reading an entire article or book to fully comprehend context, historical background, or supporting points. We’re in the days of the fast food of information: just enough to keep going, and quickly, but not a well-rounded diet of varied and deep data only decent-length writing can provide.

American education systems and parents are not the only guilty parties. Our news organizations are culpable, too. Print, radio, and television have failed us because their corporate overlords dictate which stories get regurgitated ad nauseam and which stories never make it to the light of day. President Bill Clinton failed us by signing the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which, riding hard on the Reagan-era Republican wave of deregulation, allowed conglomerates to cross-consume all media from billboards to multiple newspapers, radio stations, and television stations in one geographic area, let alone nationwide, reducing some cities—like Seattle, for example—to one-newspaper towns. Can you imagine? One editorial voice disseminating information to an entire major American city? It happened. What were we thinking? Where was the outrage? Where’s the outrage today? I’ll tell you. It’s been subverted by overtime and Netflix binge watching.

Rank-and-file teachers have historically been grossly underpaid and undervalued in the United States. I remember. I saw it my entire life with my parents, and experienced it firsthand myself. It was only in the last two decades, or so, that teachers’ salaries have been raised beyond the level that kept much of the best talent away from the pedagogical profession. Of course, since the 1990s, America’s colleges and universities have eliminated not only most tenure-track positions, but the majority of new full-time teaching positions in a measure to cut full-time benefits and pension programs due to unchecked rising healthcare costs and the need for more college sports stadiums instead of teachers and educational resources. With an army of uninvested adjunct instructors comes a further reduction in the quality of education, and so the downward cycle continues.

Because of the circles I run in, I count many good teachers as friends. For years I dated a woman who taught special education in East Harlem for the New York City Department of Education. She regularly spent her own money on school supplies for her students, put in obscene hours, and struggled to educate the most marginalized future citizens in our society: impoverished, developmentally disabled minority children. Talk about effort, patience, and sacrifice. In my twenties, I taught alongside great professors, many better than I. Before that, I studied with graduate school professors I draw inspiration from to this day. Although things are better for American educators than when I was a child, teachers today in this country are still underpaid, overworked, and undervalued. These are the people we’re hoping can create the citizens who will care for us if we can make it to retirement—another longshot that seems less likely each day for many Americans. I hope those new citizens have the skills and interest in reading articles longer than a menu, but the outlook for that isn’t good.

The Internet has bred more writers (as bloggers and email writers, primarily) than ever before, but the simple truth is neither the quality nor readership is there. Few bloggers have professional editors, for instance. The reason for that is when writing for free, what author has money to pay an editor? Again, pay me. You want a quality? You get what you pay for, but if no one has the time or attention span to read, who ultimately cares?

I’m a freak, an anomaly; part of the dying breed of readers. I long ago chose reading over television, but within that substrate I choose to read long and well-written articles over, say, a news story on Yahoo, the news site which popularized the one-sentence paragraph. Regarding journalism, the phrase “too long to read” doesn’t exist for me. That’s not true for enough American readers, and that’s a painful harbinger for my nation and her future.

Speaking of the future, I not only enjoy reading long articles, but I write them, too, and am always looking for interesting assignments. If you’ve made it this far, you know that, but most professional editors won’t, so I won’t get paid any time soon for what I do best. At almost 2000 words—for many of those editors—this is too long to read.