The Rise and Fall of the Book Superstore

by Egatz

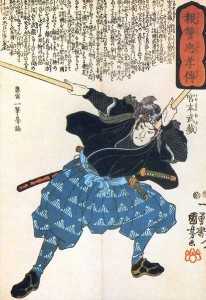

Depending which source you believe, Miyamoto Musashi was born in 1584, and was an ass-kicker of the highest order. Author of The Book of Five Rings, a martial arts textbook I still enjoy reading now and then, although I don’t swing a sword much these days, Musashi’s writing can be applied to much of our daily life today. Like Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, frustrated nonmilitary veteran corporate swine have co-opted this book and applied it to their business practices. This, of course, leads us to the business of books, which is more or less what this blog is about. Nice segue, Egatz.

Perhaps my old comrade Len Riggio would do well to track down The Book of Five Rings. Although Riggio has come a long way from his Bronx beginnings 69 years ago, times have changed, and Riggio has failed more times than not to discern this.

When I was a child, once a year my parents would make a pilgrimage to the Barnes & Noble flagship store at 18th Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City, their book-loving son in tow. This was at time when there was one bookstore in the next suburban New Jersey town; a small, cramped mom and pop affair on the first floor of a former residential home, full of charm and personal service, short on selection. As my friend David Biedny is fond of saying, as with almost everything in America since 1950, we’ve chosen convenience over quality.

In terms of convenience (read: selection), here are few words other than “magic” to describe being let loose in that Barnes & Noble. There was simply nothing else on that scale in terms of the book retail business. It was worth it to brave the insanity of Manhattan back then, with the junkies, pimps, muggers and panhandlers working their trades open and unpunished in the streets during daylight hours, often within shouting distance of disinterested police officers. My father used to put a twenty dollar bill inside his sock for emergency funds to get his family home if we were mugged. Ah, the seventies. How I don’t miss you.

Although I’m sure my childhood memories are tainted, the Barnes & Noble store seemed endless. There was a turnstile and an escalator. Multiple floors! Damn. All I previously knew were small indie bookshops and a few larger, non-anchor store chain locations in ugly malls. A trip to New York City for Barnes & Noble was special and slightly dangerous. If you survived the trip without becoming a crime victim, your wallet certainly didn’t survive.

If you couldn’t get enough of your book-fix on the West side of Broadway, you could always cross Fifth Avenue and go to the Barnes & Noble Annex, which was less polished, and where a warehouse of remainders awaited bargain hunters. Barnes & Noble was something from another world for bibliophiles.

Originally started as a printer in Wheaton, Illinois one-hundred years before my parents dragged their precocious, fucked-up only child to the book temple in Manhattan, Barnes & Noble had morphed into something her founders would not recognize. Much of the transformation was in thanks to Lenny Riggio, who parlayed his college experience of founding the Student Book Exchange at NYU in 1965 into an impressive career. Gobbling up the almost century-old Barnes & Noble in 1971, he proceeded to build it into the largest book seller in the world, largely on the concept of the superstore. The sheer scale of the Fifth Avenue retail location was refined and reproduced around the country, giving shoppers a place to get coffee and sit in a decent chair with their potential purchases.

I worked far down the Barnes & Noble food chain while I was a graduate student in the early nineties. The second year of my Master’s I shelved books at a local superstore. I quit when I found out a co-worker who couldn’t spell “Faulkner” was making a dollar more per hour than I was. Working retail is seldom fair, but then, like now, I lived for literature, and I couldn’t abide the favoritism. I wrote a letter to Lenny. I’m still waiting for a reply.

In the late eighties, Barnes & Noble opened a second and third superstore in my county. You could easily drive to all three in under twenty minutes. Like other superstores in other industries, Riggio commanded his minions to follow the Walmart strategy: move into a new location, offer tremendous discounts to attract and keep new customers, then, give them the knife. I clearly remember the standard operating procedure was thirty, then twenty-percent discounts off the cover price of both hardcover, trade paperback and paperback books. I’m talking the entire store; not just bestsellers. As the independent competition was driven out of business, sure as the sun would rise, so did the prices of the previously-discounted stock at my local superstores. I voted with my dollars at this betrayal by patronizing Borders, who offered a corporate discount. Apparently, it would take years before enough of my fellow customers did the same.

Two of those superstores remain, but they’re clearly at risk. All things involve rising and falling timing, as Musashi wrote. Riggio was on the money with his purloined Walmart strategy until the early nineties. That’s about twenty years of an extremely impressive run, but when they write the Riggio biography, the second half of his professional career will be the other side—the downslope—of that meteoric rise.

Like many other corporate businessmen, Lenny missed the Internet. It blew past his consciousness like an SR-71 overhead, taking reconnaissance photos while Riggio and crew continued to build their big box stores far below. When it was too late, Jeff Bezos and some upstarts in Washington had built and deployed a Web site where you could get virtually any book in the world, and at a discount, tax-free, and often with free shipping. Take that, brick and mortar dinosaur! By the time Barnes & Noble caught up with deploying their own Web solution, the public knew Amazon.com was the brand to trust for online book sales and a whole lot more. The greatest innovation Barnes & Noble delivered during this period was same day delivery of books to your door if you lived in Manhattan.

As Barnes & Noble continued to grow to their current size of over 700 retail outlets, including their crafty assimilation and expansion of college bookstores, they made another critical error judging the timing of harmony and discord. If you missed the information superhighway as it was laid in your neighborhood, it’s no surprise you missed the rush into the e-book market. That’s what Riggio did, and for all the hundreds of millions of dollars he and his brother Steve have made at the helm of Barnes & Noble, you’d have thought they might have hired some senior management with a little more foresight and/or technical savvy. This was clearly not the case.

The Barnes & Noble Nook followed Amazon.com’s Kindle by two years. Two years too late, and when it did appear, the Nook was slow, and the software team clearly was not staffed with anyone who had previously worked at Apple. Riggio had missed his chance to own the electronic book publishing market, and he missed it by years.

This past Tuesday, shareholders disgusted with falling stock prices and missed opportunities forced Barnes & Noble to put itself up for sale. The market cap on Barnes & Noble has fallen to under $950 million from a high of $2.2 billion. Amazon’s market capitalization stands at $57.46 billion. If Barnes and Noble was a private company, there might be hopes for a substantial turnaround. Under Wall Street’s watchful eye demanding greater and greater quarterly returns, this is impossible. Shareholders have no patience, and they will not support a retailer as it tries to reinvent itself by playing catch-up to Amazon.com, or figure out how to make an e-book reader which has an additional 200,000 apps and growing daily, like the Apple iPad.

This is not the least of the Riggio brothers’ worries. Ronald Wayne Burkle has gobbled up 19% of stock in Barnes & Noble, and Aletheia Research and Management, Inc. owns about 16%. That kind of simple math is enough to keep Len Riggio awake for many nights in a row. With stock heading for below the ten dollar mark, it looks like Burkle and Aletheia will continue their feeding frenzy, and Riggio is facing a serious challenge to his position on the board.

Although Riggio’s public face is one of optimism to keep the brand he revitalized one hundred years after it’s birth alive, this much is certain: “There is timing in the Way of the merchant, in the rise and fall of capital. All things entail rising and falling timing.” Unfortunately for the Riggio family, Lenny, Steve and those they hired were unable to discern this. It’s nothing but a matter of time before the book superstore will be thought of with nostalgia, exactly the way I think of that little suburban mom and pop bookshop on the first floor of an old residential home.

Comments

When a company first becomes successful it’s due to the reaction in the marketplace to their products. But what happens when the market shifts and they don’t? The Chicago Tribune and Barnes & Noble are prime examples of what happens when you try to stick to your Success Formula.

http://bit.ly/bSvPl3

[…] Does anyone else notice how bad the branding on the Nook is? The typemark is a lowercase sanserif “n,” which looks largely like a hump, speed bump, or a roadblock. Is that the positive image you want to get people to adopt new technology? Another blunder by Lenny Riggio and team. Keep trying guys. Maybe you’ll get it right before you’re out of jobs, but it doesn’t look promising. […]

I largely agree that the Riggio brothers should have tried to put themselves out of business by advancing technology, just as Andy Grove did with Intel; however, this would have involved transforming most of the current superstores into technology/gift/restaurants.

In otherwords, the stores would have to become destinations in which books, gifts and technology, would be high margin impulse items. I wouldn’t mind visiting Junior’s on the second floor of a

Barnes and Nobel’s and then visiting the gift shop or news stand afterwards. MMM…. cheesecake!